Healthy Ways to Handle Stress

Stressed about stress? It may be affecting your brain. Avoiding stress feels impossible. Humans will inevitably face challenges. From pandemics to parenting, life has real hurdles to deal with that aren’t going away anytime soon. The good news is that managing stress has less to do with avoiding the things that are stressing us out, and a lot more to do with how we deal with it.

At Aviv Clinics, we understand that brain health requires a holistic approach. Wellness practices that help reduce stress can be useful complements to medical therapies. The science-based Aviv Medical Program is centered on the innovative hyperbaric oxygen therapy, plus nutrition coaching and supportive practices, such as meditation, to create a wrap-around approach to enhancing cognitive and physical performance.

What is stress?

Stress is really our body’s automatic response to what it perceives to be a threat. When we encounter potential stressors, the body releases a hormone called cortisol that quickly travels throughout the body and prepares us to fight, flee, or freeze in the face of whatever stressor is threatening us.

Generally, that’s a very good thing. The system evolved to protect you from threats and keep you alive, whether you’re being chased by a sabertooth tiger, running away from an avalanche, or about to be clubbed on the head by an enemy.

The only problem? While humans have made huge advancements in terms of society and technology in the last 40 or 50 thousand years, that’s a blink of the eye in terms of our biology. Our brains are operating on outdated software that doesn’t understand how threats to our survival have changed. An argument with a spouse or a looming work deadline isn’t actually going to threaten our survival, but our lizard brains don’t know that.

Sometimes we need to engage the higher parts of our brain to understand that making a difficult phone call won’t kill us. It only feels that way and it’s okay to shut down the alert system. The problems start when we’re not able to turn off our internal alarms.

How does stress affect the body?

Stress can have both immediate and long-term effects on the body. In the short term, you may experience signs like shortness of breath, insomnia, digestive issues, brain fog, and more. There are many ways stress can affect the body in the short term.

How does stress affect the brain?

As the cortisol hormone surges throughout the body, it affects many different areas. Most of the cells in our body have cortisol receptors, but the brain is particularly packed with them. Stress primarily affects three key areas of the brain:

- The amygdala: controls your fear response and could make you feel constantly on-edge.

- The hippocampus: affects memory and learning, potentially clouding your thinking.

- The prefrontal cortex: the command center of the brain, used for problem-solving and regulating emotions.

The effects of stress are so pronounced that they can be seen in brain scans.

What’s going on during a stress response?

Once your body turns on the cortisol, several systems essentially go into “emergency mode.” Let’s say you’re hiking and out pops a big bear. Immediately, cortisol floods the body, reallocating resources as needed in order to prepare you to fight, flee, or freeze. Utilizing your nervous system, cardiovascular system, metabolism, and more, cortisol helps to supply oxygen and nutrients to areas in need, suppresses the immune system, and modulates things like appetite and satiety, attention, mood, arousal, and vigilance.

However, cortisol conveniently works as a negative feedback loop, meaning that it effectively shuts itself off when levels reach a certain point. Under ideal circumstances, your physical response to stress should reduce or stop once the threat or stressor is removed.

This means that the physiological systems in the body that work together to respond to stress have two jobs:

- to prepare the body to meet the stressor.

- to return to normal conditions when the threat is gone.

If it fails to do either of those correctly, then the body can be subjected to excessive stress that could have long-term effects on the body.

A landmark study in the 1990s by Kaiser Permanente and the Center for Disease Control (CDC) was done to look at the long-term health effects of adverse childhood events (ACEs). Examples of ACEs were things like experiencing or witnessing abuse or neglect, witnessing violence, having a loved one die by suicide, or having family members with mental health or substance abuse problems.

The study found that the number of ACEs one accumulated throughout early life directly corresponded to risk factors for a number of what are now typically referred to as stress-related diseases such as heart disease, obesity, and depression.

Stress can be good

Stress in itself isn’t inherently bad. It mostly represents a heightened state of arousal brought on by the response to stimuli, which can be negative or positive. Stress is “your body’s response to anything that requires attention or action.”

Test anxiety, for example, can improve performance in the right “dose.” If one has so much anxiety that they’re puking on their test, clearly their performance will suffer. On the other hand, someone with zero stress about the test may neglect to study at all. But just the right amount of anxiety can prompt us to take needed action.

In this way, stress can be a motivator, encouraging us to do something about a situation we want to change.

Change, as it happens, is one of the biggest causes of stress that often goes overlooked, especially when it’s a positive change.

Imagine that you just got a big promotion at work—you landed your dream job, which means a move to another state. Your long-term partner decides to go with you and thinks you should get married, so you start looking for houses. Life couldn’t be better, right? So why are you suddenly getting panic attacks?

Any major change to your routine is inherently stressful, even if it’s exciting. New jobs, big moves, and major life events like weddings and babies may be full of joy, but they still put stress on the body. That means that managing stress means managing all of its forms.

How can you treat stress?

Stress itself may not cause as many health issues as previously thought. Instead, how you react to stress may have a big impact. While some responses are considered adaptive and have positive outcomes, sometimes we may think we’re handling stress well when really it only seems that way. According to this paper on stress, “what we consider to be an adaptive short-term response may subsequently provoke long-term pathophysiological consequences.”

We all respond to stress in different ways, and we all have varying tolerance levels for stress. The same stimulus can provoke a variety of reactions from various people–what angers some people may cause sadness in others; a stressor that provokes despair from one may inspire perseverance and courage in others.

When it comes to stressful events, how you choose to think about them can impact your health. If you see a potentially stressful event as a negative situation with no possible positive outcome, it’s possible you’ll suffer more adverse health effects than if you view the situation as a challenge or opportunity to learn and grow. Thought really can affect your health.

In a study done by Harvard and UCSF, researchers sought to prove the idea of “mind over matter”; that reframing how one thinks about a situation can actually change one’s physiological response to stress.

In this experiment, three groups of people were exposed to a stressful situation and monitored before and after to judge how well they responded physically to the stress. Before the task, each group was prepared according to the experimental condition:

- One group read information explaining that stress is a natural, adaptive, and harmless response to

potential threats and that stress can actually improve performance or response to the stress. It was

emphasized that while stress was “functional and adaptive,” it was still stress. - Another group read information stating the benefits of ignoring or distracting oneself from a stressful

situation, effectively instructing them to suppress the anxiety. - A third control group was given no instruction.

Not surprisingly, the first group showed better outcomes in terms of cardiac and vascular function.

A massive related study of almost 30,000 people confirms this data.

Your perception of how stress affects you can affect your health.

The best health outcomes were observed in those people who did encounter stress but did not consider stress to be harmful; even better than people with no stress at all. Conversely, those who encountered stress and did worry about stress affecting their health showed a 43% increased risk of premature death.

Preventing and managing stress

Although we can’t avoid many of the slings and arrows that life hurls at us, we can cultivate the conditions that help us mitigate stressful situations. One of the best and still often overlooked strategies is maintaining good self-care. If we’re optimized physically, mentally, and emotionally, we put ourselves on a much better footing for dealing with challenges.

Self-care and stress have an interesting dynamic. Isn’t it strange that when we are under stress and need self-care the most, it seems to become the lowest priority? Imagine you have a ton of work to get done, all before the weekend, and I suggest that getting more sleep could help you be productive. “Get more sleep? I can’t do that, look at all the things I have to do!”

Real self-care is not wine and Netflix binges (even if they are fun in the short-term). True self-care means actively doing the things you need to do in order to maintain a happy, healthy life: watching your diet because the gut and brain are closely linked; getting enough physical activity; even simply paying your bills on time. It’s all of the less-than-fun responsibilities that come along with being a functional adult.

So how do you manage to do all of those self-care life chores without sacrificing productivity or recreation? It’s all about balance. Try this counterintuitive trick to combat stress and too-much-to-do syndrome:

Slow…down…everything…that…you…do.

Take a day or even a few hours and commit to doing everything slower by 20%. Work 20% slower. Walk 20% slower. Read 20% slower. Talk slower, breathe slower, think slower. Meditation is a great way to slow down and focus your mind also. More than likely, you’ll end up accomplishing more and enjoying yourself more in the process.

The bottom line.

The way we deal with stress matters. Stressing about stress becomes somewhat of a self-fulfilling prophecy; the more you worry about stress affecting your health, the more it can affect your health. Seeing stress for what it really is–an adaptive response that evolved to protect you from threats to your wellbeing–and practicing proper self-care can ultimately lead to better long-term health.

Stress and Gut Health: 5 tips for a happier gut and calmer life

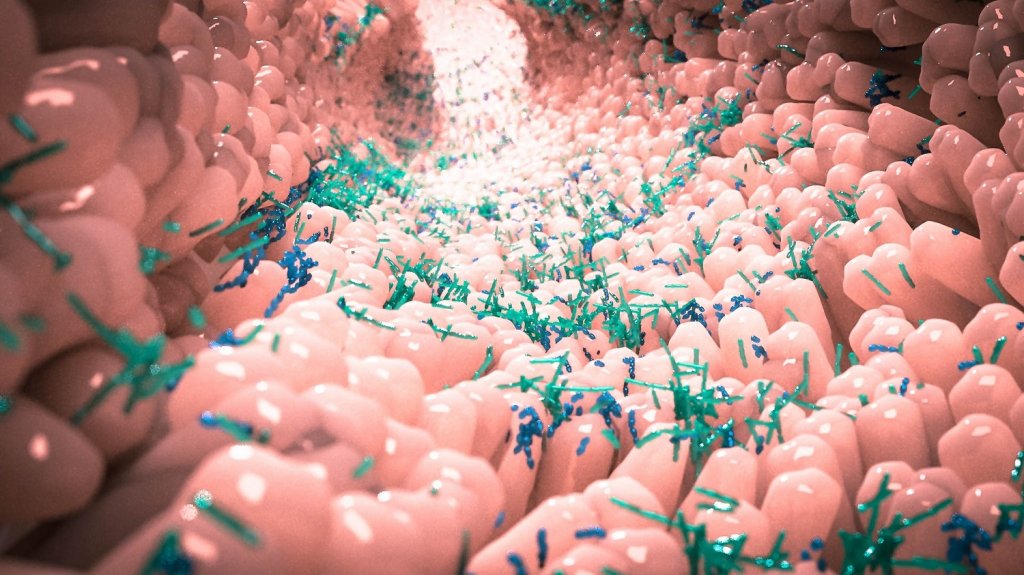

The human gut is an amazing entity. It’s home to a vast network of nerves, neural transmitters and thousands of different microflora that keep our bodies up and running. It’s so complex that scientists sometimes call it “the second brain”. It’s no surprise that stress and gut health are closely connected. Your gut can influence your moods just as much as your brain, too. Scientists are still learning how this incredibly complex system works, and there are still many things that we don’t know. We do know, however, that because the brain and gut interplay with each other, changes in one can affect the other.

High levels of stress in your body can inhibit digestion, lower your immune system and even lead to the breakdown of your intestinal lining. This can cause short term problems like diarrhea, heartburn, gas and stomach pains, or lead to more severe problems later on, like leaky gut syndrome or IBS. That’s why it’s essential to keep your stress levels under control if you want to improve your gut health.

As a center dedicated to improving cognitive health and performance, Aviv Clinics understands the importance of proper nutrition and its direct effect on your brain health. Here’s what you need to know about the brain-gut connection, along with our best tips for keeping your stress levels low and your gut bacteria content.

The Brain-Gut Connection: How stress affects the digestive system

We’ve barely scratched the surface in understanding the complex relationship of how the brain and the gut communicate to affect our moods. But here’s what we do know. Our digestive tract is home to thousands of different species of microbes all working together. This complex system works to break down the nutrients in our food, keep our immune system strong and produce hormones that keep our bodies operational. And what you put into your gut can directly affect how you feel.

Serotonin, the happiness hormone, is actually produced in the gut. It’s created by breaking down the essential amino acid tryptophan and is sent to your brain via the vagus nerve. Tryptophan is found in many whole foods like fruits, vegetables, meats, dairy and seeds. It’s one of many ways that a healthy diet can help you stay happy.

But there’s another hormone your body produces that doesn’t always make you feel good: cortisol. When your body experiences stress or discomfort, your brain triggers the adrenal gland to release cortisol, the stress hormone. Excess levels of cortisol have been linked to everything from weight gain and gastrointestinal problems to a suppressed immune system and cardiovascular diseases.

We can’t always control the things that stress us out, but we can take control of how we react to those stresses. Adopting healthy habits can help lower your cortisol levels naturally, helping you heal both your brain and your gut.

5 Tips to Strengthen your Brain-Gut Connection

- Eat whole foods

The number one thing you can do to keep your gut thriving is to eat a diet filled with whole foods. The highly-processed foods that make up the majority of our western diet lack the necessary nutrients and fiber our gut microbes need to stay healthy.

This can lead to them dying off in mass quantities, which weakens your immune system and leaves you susceptible to disease. Whole, unrefined foods like fruits and vegetables are the perfect fuel for your gut’s vast network of microflora. Their rich quantities of fiber promote proper digestion to keep your gut working properly, and a happy gut usually leads to a happy mind. It’s also important to understand the difference between good and bad sugars.

- Stop stress-eating

When we’re feeling stressed, the first thing most of us do is reach for our favorite candy or snack food to fill the void. It’s called stress-eating, and it’s a common coping mechanism for the chaos in our modern world. But although that burst of satisfaction feels good in the moment, eating sweets can exacerbate your stress-induced stomach issues in the long-term.

Foods high in refined sugar and unhealthy fats increase inflammation in the body. This sends your stress levels even higher and only worsens the problem you’re trying to cure. While there is something to be said for finding comfort in your favorite foods, stress-eating usually means you aren’t taking the time to properly enjoy your food. There’s a big difference between eating one cookie as a treat versus five because you’re eating your feelings.

The next time you find yourself craving a brownie after a stressful conversation, remember that eating sugar will only stress your belly even further. Save your indulgences for times when you can actually enjoy them instead.

- Meditate

The brain and the gut are so intricately connected that calming the brain also can calm the gut. Practicing mindfulness meditation can lower levels of cortisol in the body. These lowered stress levels can lead to improved digestion, which keeps your gut in good shape.

Taking the time to clear your mind of life’s worries can also help you be more calm and understanding in your daily life. Mindfulness meditation practices have even been proven to help with depression and anxiety, which can exacerbate other health conditions. Try meditating for just a few minutes a day and see if you feel any improvements to your nervous stomach. Here is more on meditation to get you started.

- Exercise

Working up a sweat is also an excellent way to deal with stress. In addition to obvious benefits like weight-loss and stronger muscles, exercise triggers the release of serotonin, which can lower stress levels. Even a 20-minute stroll outside can do the trick to get the serotonin flowing. Just be careful to pace yourself, and be sure not to overdo it.

- Get more sleep

Sleep is the essential time period when our bodies take time to recharge every day. Getting a good night’s rest can improve your cognitive performance and help fight off Alzheimer’s disease. Getting adequate rest is also important for lowering stress levels, and you can improve the quality of your sleep by improving your diet.

Eating foods high in tryptophan helps your gut produce serotonin and also leads to the production of melatonin, the sleep hormone. Higher levels of melatonin can dramatically improve the quality of your rest, which can work to lower stress in your body. If you want to get a better night’s sleep, try eating more fruits and vegetables during the day.

The Bottom Line

Stress and gut health are closely linked. Eating healthy whole foods is one of the best things you can do to reduce your stress levels and stomach issues. Treats may be enjoyed in moderation, but not to fill an emotional void or coping mechanism for stress.

The Gut-Brain Connection

With much information available about “gut health” these days, it is difficult to know what’s real and what’s just hype. Data emerging from recent scientific research strongly suggests that gut health matters–much more than we previously thought. The trillions of microbes that live in your gut may play a key role in keeping you healthy. Some scientists now treat the gut microbiome like an organ system, as important as our respiratory or circulatory systems.

Gut flora works in symbiosis with other organ systems, which means the gut could impact–and even prevent–numerous diseases and conditions. Autoimmune disorders, Alzheimer’s, heart disease, cancer, and even depression have all been associated with gut health.

For this reason, innovative centers such as Aviv Clinics use a customized nutrition plan as an integral part of the medical treatment protocol for clients seeking to improve their cognitive and physical performance, or symptoms of conditions like fibromyalgia, Lyme, dementia, traumatic brain injuries, and brain fog.

The health of your gut microbiome is important for your brain health

As scientists continue to study our complex brains, we are learning that the brain’s functions extend far beyond the skull. We increasingly find that the brain is deeply connected to the entire body, especially the gut. We can’t talk about brain health or brain function without including gut health and function. It’s exciting news for anyone struggling with neurological or psychological disorders. Could the secrets behind mysterious, complex, or debilitating conditions reveal themselves in the gut?

So what is going on in the gut, and how does it affect our health?

What is the microbiome?

Your gut is home to over 100 trillion microbes, collectively called the microbiome or gut flora.

With more than 1000 species of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa in your gut flora, they outnumber your human cells by 10 to 1!

Each microorganism in your body also contains DNA; added up, the microbiome turns out to contain 200 times the amount of genetic material in our own human cells. In fact, according to the University of Washington, “autoimmune diseases appear to be passed in families not by DNA inheritance, but by inheriting the family’s microbiome.”

The gut (via the mouth) is an entry point into the body, and the microbiome helps to keep out invaders by maintaining the intestinal barrier. This barrier acts as a filter to let in nutrients and keep out pathogens and helps us digest our food, providing nutrients we’d otherwise be unable to harvest.

Are there “good” and “bad” microbes?

If the thought of trillions of bacteria hanging out in your body seems scary, don’t worry–generally, our guts are inhabited by commensal or so-called “good” bacteria and other microbes. Calling some microbes good and others bad is an oversimplification. Most microbes are harmless, and even the ones that may cause harm don’t always do so. The same species of microbe might be completely harmless under most conditions, but potentially cause disease under different conditions. In the gut of an otherwise healthy person, the potentially harmful microbes reside in small numbers and are kept in check by other microbe species.

What makes a healthy gut?

Science can’t answer this definitively, because everyone’s microbiome is unique. It’s not about one species of microbe or even a certain combination; what a healthy gut looks like varies from person to person.

“It would be great if we could identify 10 or so bacteria and say these are the ones you need most, but it doesn’t work that way, and there is no magic bullet,” says Dr. Elizabeth Hoffman, an infectious disease doctor from Massachusetts General Hospital.

What healthy guts have in common is diversity. They are colonized by a wide variety of microbial species. Assessing the health of the microbiome is about the balance and stability in the entire “ecosystem” of the gut. When this balance is thrown off, the microbiome can shift into a state of dysbiosis, where its normal supportive functions in the body get disrupted. As a result, the body becomes even more susceptible to disease and dysregulation.

What causes gut dysbiosis?

Many factors have been found to cause gut dysbiosis: environmental factors like stress, diet, medications such as antibiotics, illness or disease, or even “inflamm-aging” can throw off the balance. Neurological and psychological conditions are being associated more and more with gut dysbiosis. By understanding the physical and functional links between the brain and the gut, we can see how their fates seem to be intertwined.

Your second brain

Butterflies in your stomach is one example of the gut-brain connection. If you’ve had digestive issues in stressful times, it’s not just coincidence. Our thoughts and feelings really can influence our health by directly altering the gut. Neurons, which we typically think of as only residing in the brain, actually line our gastrointestinal tract and branch into our stomach and intestines. With over 500 million neurons, the enteric nervous system (ENS) is sometimes referred to as the “little brain” in our gut. This neural matter doesn’t contribute to thinking or consciousness, but it is part of a robust pathway for two-way communication between the big brain in your skull and your microbiome known as the Gut-Brain Axis (GBA).

The Gut-Brain Axis is a complex two-way channel of communication between the brain and the gut and involves the limbic system, central nervous system (CNS), autonomic nervous system (ANS, our flight or fright system), ENS, immune system, hormones, and more. Whatever is going on in your head, including emotions, behavior, and even thoughts, could partially be affected by what’s going on in your gut, and vice versa. If we want to understand neurological conditions, we can’t just study the brain. Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s, depression and anxiety, and even “motivation and higher cognitive functions” all have been linked to the gut microbiome. The gut microbiome presents an area for more research that may be the key to treating these disabling conditions.

How does the gut affect the brain?

One of the gut’s primary roles is the production and turnover of neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. Up to 95% of serotonin is produced in the gut. The gut also maintains the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier, which acts as a filter to keep out bad stuff while letting in nutrients. If this barrier gets disrupted, invaders can infiltrate the body and promote inflammation and exacerbate many autoimmune disorders. Gut flora also produces a metabolite called short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) that are integral in gut-brain signaling. When this signaling malfunctions, it can contribute to nervous system disorders, ranging from neurodevelopmental disorders to neurodegenerative diseases.

How the brain affects the gut

The microbes in our gut have receptors on their surface designed to interact with the neurotransmitters produced in the brain. Stress can directly affect your neurotransmitters, which can go on to influence the gut flora and its habitat. Stress also can change the total mass of the microbiota and the composition of species, an important factor in overall gut health.

The GBA may control and respond to stress through our hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis, which involves hormones like cortisol. One theory of depression is that overactivation of the HPA axis often causes heightened levels of cortisol. The brain can also affect the gut by changing the habitat for the microbiome. This includes mucosal secretions in the intestines, altering how fast your bowels move, and other environmental conditions. It can also directly affect what enters your body from the outside and immune function.

Keep your gut happy, and it keeps you healthy

Here are a few tips:

Diet: It’s all about diversity. Eat a wide variety of foods for a healthier microbiome.

Stress: Keep your stress in check. When you’re stressed, your microbiome is stressed. It’s easier said than done, but worth the effort.

Antibiotics: While useful for fighting infections from harmful bacteria, antibiotics also often kill some of the good bacteria in your gut. Antibiotics have been shown to throw the microbiome into dysbiosis.

Probiotics and Prebiotics: Probiotics and prebiotics work together. Probiotics contain good bacteria that could correct gut dysbiosis. Probiotics also may improve depression and anxiety after just 30 days. Prebiotics are healthful carbohydrates and fiber from fruits and vegetables that help feed your probiotics. The more colorful your diet, the healthier it is likely to be.

The bottom line:

The discovery of the Gut-Brain Axis tells us that your thoughts and feelings, along with your overall environment and experiences, all play into the health of the gut, which can directly impact your overall health.

Aviv Clinics delivers a highly effective, science-based treatment protocol to enhance brain performance and improve the cognitive and physical symptoms of conditions such as traumatic brain injuries, fibromyalgia, Lyme, and dementia. The Aviv Medical Program’s intensive treatment protocol uses Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy and includes nutrition management and dietitian support to optimize your diet for better brain health. Based on over a decade of research and development, the Aviv Medical Program is holistic and customized to your needs. Contact us to learn more.